After last week’s story about Seacliff, and the quest for documents, I’ve had email after email from people looking for answers for their loved ones.

That included a couple of readers who shared that they previously had the sealed file of their relatives released, after long-running battles with the SDHB.

Some of the content they found was confronting, but that’s for another time.

The shadow of Seacliff seems to be following me around at the moment.

On Sunday, I took the family to Bruce Mahalski’s Museum of Natural Mystery

It was incredible.

If you go, and I recommend it, take your time and read everything.

The museum includes several items connected with Seacliff, and that sparked many questions (too many . . . ) from my boys (7 & 13), about the former institution.

This week I also received an email from a reader, seeking help with another story.

You might remember this one, it involved the brutal murder of Nurse Peggy McInnes, a former nurse at Seacliff who was killed at Orokonui Hospital - a former psychiatric hospital about halfway between Dunedin and Seacliff - on August 24, 1928.

It turns out the reader (thanks Viv!) has a connection to that murder.

Her great grandfather, Thomas Ashworth, was the person who found both Peggy and the man who killed her, Dunedin bricklayer, Thomas Ellis.

And that’s not all.

Ashworth later wrote a memoir, which documented across five pages his experience of that terrible night.

I was stunned.

Ashworth was in charge of a ‘bush gang’, which was six Seacliff patients, who would help cut firewood, fencing, build bridges, and help with farming.

‘‘It was hard, healthy work,’’ Ashworth wrote.

He later took over a night shift due to another person going on holiday, around the time of the murder.

‘‘One night I had done the midnight round and was going to the end of the avenue to see that the oil lamps on the road were burning.’’

As there was no electricity on the roads around Waitati, that meant the man on night duty had to carry a lamp.

Near a plantation of pine trees and blackberry bushes: ‘‘I heard some thrashing about, but couldn’t make out what it was; I knew that an inmate hadn’t got out, and it wasn’t loud enough for a horse and cow to be there’’.

‘‘I just stood for a time and then I heard some groaning.’’

Ashworth called out, but got no response: ‘‘so there was only one thing to do’’.

‘‘Go and find out.’’

He grabbed a stout stick and went to explore among the blackberries where: ‘‘I saw a man moving about’’.

The man did not answer Ashworth, who in the darkness thought he was drunk.

‘‘I put the lamp on the ground as I wanted my hands free in case he attacked me.’’

But the man stayed silent, and it was only when Ashworth dragged him towards the light that he saw he had ‘‘a bad gash in his throat’’.

‘‘He was alive but I could see he couldn’t last long.’’

Ashworth ran to fetch a doctor, ‘‘but he was dead when I got back’’.

He and another attendant took the dead man to the morgue, before calling police.

Ashworth continued with his jobs, which included walking around the outside of the female wards, and stoking the boilers.

But he rang the night nurse to ask her to look after the boilers, explained what had happened, and made himself a cup of tea as he waited for police.

That break was interrupted when the phone rang. It was the matron, who told him a female nurse had gone out earlier that evening with a man and who was ‘‘going to break it off’’.

Ashworth then stepped out into the night again: ‘‘to see if I could find any trace of her’’.

‘‘After some time I found her, but she was dead. I won’t go into detail here, (too gruesome) other than to say there was a lot of blood about.’’

It was then when he heard the police officer and another attendant arrive, and Ashworth once again helped take a body to the morgue.

His long night was not over, there was blood to be cleaned, a statement to make, and bodies to be identified.

By daylight he had finished.

‘‘It had been a hectic night and I was dog tired, so had some breakfast and went to bed.

‘‘I didn’t get much sleep, and reporters came a short time later.

‘‘They wanted to know everything.’’

He also spoke again with police, and soon was back on duty.

It was back at work when the doctor told him just to do a half shift.

Ashworth recalled the inquest being a ‘‘nasty experience’’, as was trying to get a replacement uniform due to his being torn on blackberry bushes.

‘‘With Government departments being what they are, I had as much trouble getting that, as if I was trying to get a multi-million dollar contract.’’

That involved writing a letter to the accountant at Seacliff, which was then sent to Wellington, and later it was asked whether he could just get the stains out.

It took two months to get a replacement pair of trousers.

This week I interviewed Vanessa Carswell, a principal and registered architect with Jasmax, in Christchurch.

If you haven’t heard of Jasmax by now, you probably will.

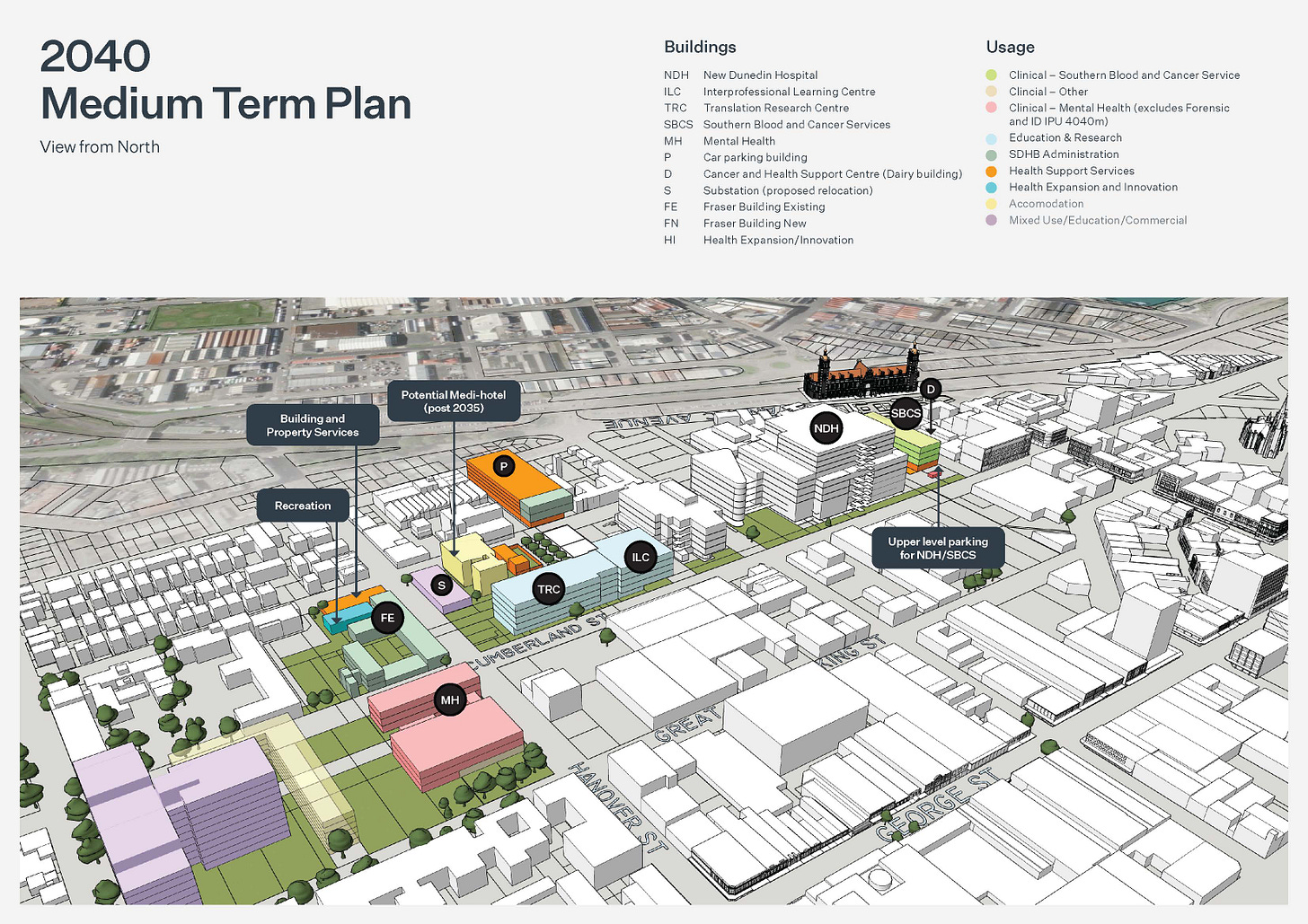

That is because the architecture and design firm is involved in the design of both the George St project and the health precinct masterplan, called Te Whakaari (The Promise).

The latter involves the environment around the city’s new hospital, and includes creating green spaces, additional education and healthcare facilities and recreation areas.

Carswell had worked in Dunedin ‘‘on and off’’ for over a decade on a diverse number of projects.

She understood why some residents may be anxious about the projects, which included a large empty space where the former Cadbury factory once stood.

That site, which will form part of the Dunedin Hospital rebuild, along with the wider precinct and George St redevelopment, would ‘‘be the sort of activity that Dunedin hasn’t really seen before’’.

Dunedin presented some unique challenges; the CBD was nestled between the surrounding hills and harbour, and featured a one-way system.

‘‘It is very much oriented around the vehicle, and how to get through the city . . . not really interact with the city.’’

Part of the challenge was about improving how people moved through the city, and doing that better, particularly at a time when Dunedin was experiencing growth, Carswell said.

That wasn’t just for cars, but for other modes of transport, and it was important to take a long-term view ‘‘to create the sort of cities that we really want to live in’’.

‘‘We won’t be as car-dominated as we are today, in the future . . . we need to start planning for that now.’’

And with the increasing move to online shopping, it meant it was important to make the central retail street, which starts with the ‘Farmers’ block’, into a destination.

Jasmax was involved in the landscape and design of George St Retail Upgrade.

‘‘We need to think of how we are going to create a city that is better for our children, and our children’s children, and create an environment that may give something back.’’

That included not only making the inner city more livable, but regenerating the environment.

Dunedin’s CBD was a healthy one, unlike other major centres it did not feature suburban malls that had stripped retailers from the traditional shopping streets.

Dunedin was also fortunate that the gold rush era led to well built buildings dominating the streetscape, but missed some of the cruder developments of the 60s to 80s.

But that colonial era of the gold rush did ‘‘white wash’’ a lot of what was important to Māori, including the changing of topography, and renaming of places, she said.

Now a significant feature of the Dunedin redesign was working with mana whenau to ‘‘rebalance that a bit’’.

Carswell said she was delighted with the feedback received on both projects, which was overwhelmingly positive.

The previous makeover for George St was in the 1990s, and was largely about replacing pavers: ‘‘but this is a very significant change’’.

That included George St becoming a one-way south, with Carswell having no preference for what council ultimately decided.

‘‘We will leave it to the experts and the decision-makers to make those calls.’’

She noted that the city’s decision-makers were reasonably aligned with their strategic thinking and shared vision.

That included the health precinct master plan, which spanned a period over 60 years.

Once the new hospital was completed, Dunedin would have the country’s best hospital, which would also double as an important training facility for New Zealand’s future healthcare staff.

‘‘It has the opportunity to influence and effect how healthcare is provided nationally.’’

The aim of both projects was to make Dunedin an attractive place for residents and visitors.

A ‘‘green spine’’ along the healthcare precinct would also make the area a more pleasant place .

The changes in Dunedin differed to that in Christchurch’s CBD, which was driven in response to the devastating earthquakes.

The ability to plan ahead meant Dunedin could also plan for the required workforce, rather than rush into major projects at the same time, leading to a shortage of skilled labour.

‘‘Dunedin has a big advantage in that it is thinking about that now.’’

Great to hear.

It was also cool to hear about the water and light show for the inaugural Matariki holiday.

It sometimes feels that events are increasingly a rarity in these pre-Covid times, so this is extra special.

Over three nights, 24-26 June, Mana Moana: Ōtepoti will offer a ‘‘breath-taking and poignant cinematic experience on the Otago Harbour waterfront’’, according to the press release.

But wait, there is more.

It is free!

The Dunedin City Council-funded event would feature the work of Māori and Pāsifikā artists through images, short film, poems, dance and more, all projected onto a water screen.

More details here.

And here is a 12 minute clip of a person walking around the Northern Cemetery.

Check this great historic pix in my Tweet of the Week.

That’s a beautiful pix.

In case you missed it we are in the middle of New Zealand Music Month, so I recommend having a listen to some new tunes.

Local band Asta Rangu is one of those, and they have a new track called LLPLZA

Now time for a ‘pop’ quiz:

The press release for the band says it was ‘‘Inspired by Stereolab's use of marimba and vibraphone to accent melodies, LLPLZA is four minutes of layered texture and tweaked tones that culminate in a reflective joy’’.

Can you name a Dunedin person who was once a member of that famous band?

Please answer in the comments below.

Have a great week, and stay healthy!

Andrew Brough?

Steve MacNamara?